No edit summary |

Tag: Visual edit |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

===Forced into Propaganda=== |

===Forced into Propaganda=== |

||

| − | Even though the Hindenburg was designed for passengers, unfortunately, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazi_Party the Nazi Party] (soon to be the world's most evil political party) heard of the new airship. Hearing that it was going to be the largest in the world, the Nazi's wanted to use the airship as a symbol of Nazi propaganda. The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda |

+ | Even though the Hindenburg was designed for passengers, unfortunately, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazi_Party the Nazi Party] (soon to be the world's most evil political party) heard of the new airship. Hearing that it was going to be the largest in the world, the Nazi's wanted to use the airship as a symbol of Nazi propaganda. The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda had been using airships for propaganda. The Hindenburg and the Graf Zeppelin were designated by the government as a key part of the process. |

| − | However, an angry Dr. Hugo Eckner was against using his airships for propaganda, as he was against the Nazi regime and he thought that being used for propaganda made the Zeppelin company look bad. The |

+ | However, an angry Dr. Hugo Eckner was against using his airships for propaganda, as he was against the Nazi regime, and he thought that being used for propaganda made the Zeppelin company look bad. The Nazis, however, made orders for the airship to still be used as a symbol of propaganda by painting the Swastika, the Nazi's official symbol, and the tailfins of the Hindenburg. They also helped fund the Zeppelin company during a financial crisis, eventually forcing the Zeppelin company to follow their orders. So, a frustrated Eckner had his employees paint the Swastika on the tail fins of the ship. |

==Trial Flights== |

==Trial Flights== |

||

In 1936, the Hindenburg was complete, five years after construction began in 1931. Dr. Hugo Eckner announced the [[File:45-LZ-129-March-1936-tw-550x378.jpg|thumb|382px|The Hindenburg flies for the very first time.]]airship's name before the test flight, though he had picked the name a year ago, as a dedication to the previous president of Germany, Paul von Hindenburg. The Hindenburg maiden trial voyage was on March 4th, 1936. The Hindenburg took off from the Zeppelin dockyards at Friedrichshafen on with 87 passengers and crew members on board. These included the Zeppelin Company chairman, Dr. Hugo Eckener, as commander, former World War I Zeppelin commander Lt. Col. Joachim Breithaupt representing the German Air Ministry, the Zeppelin company's eight airship captains, 47 other crew members, and 30 dockyard employees who flew as passengers. Harold G. Dick was the only non-Luftschiffbau representative aboard. At the time of the flight, the ship's logo hadn't been painted on yet, though it's registration ID (D-LZ129) had been painted. The Hindenburg also had the Olympic rings painted on its side as the 1936 [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1936_Summer_Olympics Berlin Olympic Games] were to be going on that year. |

In 1936, the Hindenburg was complete, five years after construction began in 1931. Dr. Hugo Eckner announced the [[File:45-LZ-129-March-1936-tw-550x378.jpg|thumb|382px|The Hindenburg flies for the very first time.]]airship's name before the test flight, though he had picked the name a year ago, as a dedication to the previous president of Germany, Paul von Hindenburg. The Hindenburg maiden trial voyage was on March 4th, 1936. The Hindenburg took off from the Zeppelin dockyards at Friedrichshafen on with 87 passengers and crew members on board. These included the Zeppelin Company chairman, Dr. Hugo Eckener, as commander, former World War I Zeppelin commander Lt. Col. Joachim Breithaupt representing the German Air Ministry, the Zeppelin company's eight airship captains, 47 other crew members, and 30 dockyard employees who flew as passengers. Harold G. Dick was the only non-Luftschiffbau representative aboard. At the time of the flight, the ship's logo hadn't been painted on yet, though it's registration ID (D-LZ129) had been painted. The Hindenburg also had the Olympic rings painted on its side as the 1936 [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1936_Summer_Olympics Berlin Olympic Games] were to be going on that year. |

||

Latest revision as of 03:03, 10 October 2019

The LZ 129 Hindenburg (Registration: D-LZ 129) was a large German commercial passenger-carrying rigid airship, the lead ship of the Hindenburg class, the longest class of flying machine, and the largest airship by envelope volume. It was designed and built by the Zeppelin Company on the shores of Lake Constance in Friedrichshafen and was operated by the German Zeppelin Airline Company. The airship was designed by airship pilot and designer, Hugo Eckener. The airship flew from March 1936 until it was destroyed by a massive fire 14 months later on May 6, 1937, while attempting to land at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Manchester Township, New Jersey, at the end of the first North American transatlantic journey of its second season in service with the loss of 36 lives. This was the last of the great airship disasters; it was preceded by the crashes of the British R38in 1921 (44 dead), the US airship Roma in 1922 (34 dead), the French Dixmude in 1923 (52 dead), the British R101 in 1930 (48 dead), and the USS Akron in 1933 (73 dead).

Hindenburg was named after the late Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, President of Germany from 1925 until his death in 1934.

Construction History[]

Design[]

The Hindenburg was to be part of a series of airships known as "the Hindenburg class." Originally known as the LZ 128, the Hindenburg's design began planning after the Graf Zeppelin's round trip around the world, as commercial airship travel had spiked up in popularity. This ship was to be approximately 776 ft (237 m) long and carry 5,000,000 cu ft (140,000 m3) of hydrogen (the gas that gave many airships lift at their time). The hydrogen would be stored in gas bags within the ship's metal framework, like all zeppelins at that time (blimps did not have gas bags; the air was just blown up in the fabric, like a giant balloon. Ten Maybach engines were to power five tandem engine cars (a plan from 1930 only showed four engine cars).

However, the design was decided to be redone, in 1930, because the R101, a British passenger airship, got caught in a bad storm, with the stormy winds ripping open the fabric of the airship. This tore two holes in the gas bags (which stored the hydrogen need to create lift) causing a hydrogen leak that sent the ship falling towards the ground. The ship crashed at less than 13 mph, but the metal nose crumpled, scraping together, creating sparks which ignited the leaking hydrogen, setting the entire airship on fire. It was destroyed in less than a minute, killing 48 of the 54 passengers and crew on board. This ended the British Airship Program (main articles R101 and R101 Disaster).

To greatly reduce the risk of fire, the second design, the LZ 129, was to be designed to hold helium in the gas bags

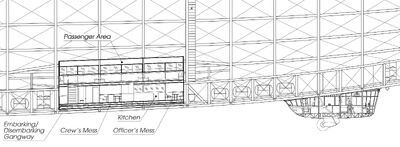

The Hindenburg's Passenger Quarters and Crew Car Gondola

instead, as it was less flammable. Initial plans projected the LZ 129 to have a length of 813.67 feet (248.01 m), but 10 feet was dropped from its tail in order to allow the ship to fit in Lakehurst Hangar No. 1.

The Hindenburg had a duralumin structure, incorporating 15 Ferris wheel-like main ring bulkheads along its length, with 16 cotton gas bags fitted between them. The bulkheads were braced to each other by longitudinal girders placed around their circumferences. The airship's outer skin was of cotton doped with a mixture of reflective materials intended to protect the gas bags within from radiation, both ultraviolet (which would damage them) and infrared (which might cause them to overheat.

The Map of the Hindenburg

The Hindenburg was also streamlined, like many airships at the time, like the R101. A streamlined airship means that instead of having the gondola holding both the passengers and the crew and being separated from the metal structure to house the floating gas (like blimps or other zeppelins, like the Graf Zeppelin), the gondola would be smaller and house the crew, while the passengers section would be built into the metal framework, just below the gas cells. Unlike blimps, like all other zeppelins, crew members (and sometimes passengers with permission) had walkways built within the metal structure around the gas bags along, with separate rooms to hold cargo, and other vital controls to the airship. The passengers quarters were also built with high luxuries, like ocean liners at the time. Hindenburg's interior furnishings were designed by Fritz August Breuhaus, whose design experience included Pullman coaches, ocean liners, and warships of the German Navy. The upper "A" Deck contained small passenger quarters in the middle flanked by large public rooms: a dining room to port and a lounge and writing room to starboard. Paintings on the dining room walls portrayed the Graf Zeppelin's trips to South America. A stylized world map covered the wall of the lounge. Long slanted windows ran the length of both decks. The passengers were expected to spend most of their time in the public areas, rather than their cramped cabins.

The Hindenburg's interior before the gas bags were installed.

The lower "B" Deck contained washrooms, a mess hall for the crew, and a smoking lounge. Harold G. Dick, an American representative from the Goodyear Zeppelin Company, recalled "The only entrance to the smoking room, which was pressurized to prevent the admission of any leaking hydrogen (once the gas was changed from helium to hydrogen), was the bar, which had a swiveling airlock door, and all departing passengers were scrutinized by the bar steward to make sure they were not carrying out a lit cigarette or pipe.

Changing from Helium to Hydrogen[]

As mentioned before, helium was going to be the original choice of gas for the Hindenburg, as it was much safe. They also made plans, in order to reduce the budget and increase more lift in the airship, saying that 14/16 gas cells would be filled with helium, while the other 2 would be filled with hydrogen, showing little risk to fire. However, in 1927, the United States signed a ban on exporting helium to other countries, as wartime risks built up over the next few years with Germany. Many U.S officials feared that the Nazi's, which were starting to rise in power, would use helium to create destructive weapons. Also, the United States owned most of the helium at the time, so it was hard to come by in other countries.

This caused the helium to be very expensive and obsolete. However, the Zeppelin company still tried to convince the U.S to lift the ban, but the U.S turned them down, as they were fearful of Adolf Hitler's rise to power. So, without changing much of the design, the Hindenburg went back to using the normal gas for German airships at the time; hydrogen. It was cheap to buy and it provided more life. Eckener was concerned, as many hydrogen-filled airships in the past had been destroyed disastrous fires, as hydrogen was highly flammable (as mentioned above). However, most Germans weren't worried, as they had always been flying hydrogen airships for years and never had an accident, injury or death, leading to the widely held belief they had mastered the safe use of hydrogen. As many Germans said, "We know this is a risky gas, but if you take the right precautions like us, you can control the risk."

Forced into Propaganda[]

Even though the Hindenburg was designed for passengers, unfortunately, the Nazi Party (soon to be the world's most evil political party) heard of the new airship. Hearing that it was going to be the largest in the world, the Nazi's wanted to use the airship as a symbol of Nazi propaganda. The Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda had been using airships for propaganda. The Hindenburg and the Graf Zeppelin were designated by the government as a key part of the process.

However, an angry Dr. Hugo Eckner was against using his airships for propaganda, as he was against the Nazi regime, and he thought that being used for propaganda made the Zeppelin company look bad. The Nazis, however, made orders for the airship to still be used as a symbol of propaganda by painting the Swastika, the Nazi's official symbol, and the tailfins of the Hindenburg. They also helped fund the Zeppelin company during a financial crisis, eventually forcing the Zeppelin company to follow their orders. So, a frustrated Eckner had his employees paint the Swastika on the tail fins of the ship.

Trial Flights[]

In 1936, the Hindenburg was complete, five years after construction began in 1931. Dr. Hugo Eckner announced the

The Hindenburg flies for the very first time.

airship's name before the test flight, though he had picked the name a year ago, as a dedication to the previous president of Germany, Paul von Hindenburg. The Hindenburg maiden trial voyage was on March 4th, 1936. The Hindenburg took off from the Zeppelin dockyards at Friedrichshafen on with 87 passengers and crew members on board. These included the Zeppelin Company chairman, Dr. Hugo Eckener, as commander, former World War I Zeppelin commander Lt. Col. Joachim Breithaupt representing the German Air Ministry, the Zeppelin company's eight airship captains, 47 other crew members, and 30 dockyard employees who flew as passengers. Harold G. Dick was the only non-Luftschiffbau representative aboard. At the time of the flight, the ship's logo hadn't been painted on yet, though it's registration ID (D-LZ129) had been painted. The Hindenburg also had the Olympic rings painted on its side as the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games were to be going on that year.

Her first test flight ended successfully. Her second test flight was on March 26th, 1937. As the airship passed over Munich during the flight, the city's Lord Mayor, Karl Fiehler, asked Eckener by radio the LZ129's name, to which he replied "Hindenburg". On March 23, Hindenburg made its first passenger and mail flight, carrying 80 reporters from Friedrichshafen to Löwenthal. The ship flew over Lake Constance with Graf Zeppelin. The name Hindenburg lettered in 6-foot-high (1.8 m) red Fraktur script (designed by Berlin advertiser Georg Wagner) was added to its hull three weeks later before the Deutschlandfahrt on March 26, no formal naming ceremony for the airship was ever held. The airship was operated commercially by the Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei (DZR) GmbH, which had been established by Hermann Göring in March 1935 to increase Nazi influence over airship operations. The DZR was jointly owned by the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin (the airship's builder), the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (German Air Ministry), and Deutsche Lufthansa A.G. (Germany's national airline at that time), and also operated the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin during its last two years of commercial service to South America from 1935 to 1937. The Hindenburg and its sister ship, the LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II (launched in September 1938), were the only two airships ever purpose-built for regular commercial transatlantic passenger operations, although the latter never entered passenger service before being scrapped in 1940. The Hindenburg made a total of six successful test flights during March of 1936.

Die Deutschlandfahrt Propaganda Flight[]

Just before the final endurance test flight, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels demanded that the Zeppelin Company make the two airships available to fly "in tandem" around Germany over the four-day period prior to the voting with a joint departure from Löwenthal on the morning of March 26, 1936. While gusty wind conditions that morning would prove to make the process of safely launching the new airship a difficult one, Hindenburg's commander, Captain Ernst Lehmann, was determined to impress the politicians, Nazi party officials, and press present at the airfield with an "on time" departure and thus proceeded with its launch despite the adverse conditions. As the massive airship began to rise under full engine power it was caught by a 35-degree crosswind gust, causing its lower vertical tail fin to strike and be dragged across the ground, resulting in significant damage to the bottom portion of the airfoil and its attached rudder. Eckener, who had opposed the joint flight both because it politicized the airships and had forced the cancellation of the essential final endurance test for Hindenburg, was furious and rebuked Lehmann.

Graf Zeppelin, which had been hovering above the airfield waiting for Hindenburg to join it, had to start off on the propaganda mission alone while LZ 129 returned to its hangar. Their temporary repairs were quickly made to its empennage before joining up with the smaller airship several hours later. As millions of Germans watched from below, the two giants of the sky sailed over Germany for the next four days and three nights, dropping propaganda leaflets, blaring martial music and slogans from large loudspeakers, and broadcasting political speeches from a makeshift radio studio aboard Hindenburg. This was one of the first times the Hindenburg was filmed on camera.

Sadly for Eckener, his name would "no longer be mentioned in German newspapers and periodicals" and "no pictures nor articles about him shall be printed." This action was taken because of Eckener's opposition to using Hindenburg and Graf Zeppelin for political purposes during the Deutschlandfahrt, and his "refusal to give a special appeal during the Reichstag election campaign endorsing Chancellor Adolf Hitler and his policies." The existence of the ban was never publicly acknowledged by Goebbels, and it was quietly lifted a month later.

Passenger Service[]

First Flight[]

After the propaganda flight, the Hindenburg went to work as a commercial passenger zeppelin. Its first commercial flight was from Löwenthal to Rio de Janeiro. This was also its first transatlantic flight. Hugo Eckener was not to be the commander of the flight, however, but was instead relegated to being a "supervisor" with no operational control over Hindenburg while Ernst Lehmann had command of the airship. It departed on March 31st, 1936. The Hindenburg arrived in Rio on April 4th, 1936. There was lots of fanfare from reporters and spectators, wanting to view the world's largest airship. While at Rio, the crew noticed one of the engines had noticeable carbon buildup from being run at low speed during the propaganda flight days earlier. The airship took off for its return flight back to Germany on April 6th. During the flight, the automatic valve for gas cell 3 stuck open. Gas was transferred from other cells through an inflation line. It was never understood why the valve stuck open, and subsequently, the crew only used the hand-operated maneuvering valves for cells two and three. 38 hours after departure, one of the airship's four Daimler-Benz 16-cylinder diesel engines (engine car no. 4, the forward port engine) suffered a wrist pin breakage, damaging the piston and cylinder. Repairs were started immediately and the engine functioned on fifteen cylinders for the remainder of the flight. Four hours after engine 4 failed, engine no. 2 (aft port) was shut down, as one of two bearing cap bolts for the engine failed and the cap fell into the crankcase. The cap was removed and the engine was run again, but when the ship was off Cape Juby the second cap broke and the engine was shut down again. The engine was not run again to prevent further damage. With three engines operating at a speed of 62.6 miles per hour (100.7 km/h) and headwinds reported over the English Channel, the crew raised the airship in search of counter-trade winds usually found above 5,000 feet (1,500 m), well beyond the airship's pressure altitude. Unexpectedly, the crew found such a wind at the lower altitude of 3,600 feet (1,100 m) which permitted them to guide the airship safely back to Germany after gaining emergency permission from France to fly a more direct route over the Rhone Valley. There was no commotion in the passengers quarters. The four-day flight covered 12,756 miles (20,529 km) in 103 hours and 52 minutes of flight time. The airship landed safely without trouble on April 10th Löwental. All four engines were later overhauled and no further problems were encountered on later flights. For the rest of April, Hindenburg remained at its hangar where the engines were overhauled and the lower fin and rudder received a final repair; the ground clearance of the lower rudder was increased from 8 to 14 degrees.

First Flight to the United States[]

The Hindenburg arrives at Lakehurst for the very first time.

The Hindenburg's golden age of service began in May. The airship first had a day-long flight from Löwental to Friedrichshafen, to pick up passengers on the Hindenburg's first-ever flight to the United States of America. The ship then set off to one of the world's best-known airship fields; Lakehurst, New Jersey.

The passengers on Hindenburg’s maiden voyage to America included celebrities, wealthy travelers, journalists, and members of the Nazi elite. This was also the first time a church mass was ever done on the airship, and the first time the Hindenburg's grand piano was on board. The piano was different than normal grand pianos. Instead of being made out of hard rock maple wood like normal pianos, it was made out of aluminum, which is lighter than hard maple, which is better to have lighter furniture on an airship. What's also amazing is that a radio report from NBC was broadcasted on the airship during its flight, also including a concert from the ship's aluminum, piano.

Hindenburg’s 2-1/2 day crossing of the North Atlantic was an astounding accomplishment at a time when even the fastest transatlantic ocean liners (such as the Blue Riband-winning Queen Mary, Normandie, and Bremen) made the trip in five days, and slower ships took as long as 10 days. It was even faster than normal airships.

The airship arrived in Lakehurst, New Jersey with massive crowds to watch the landing. The landing went without a single mishap. Once the ship was docked to the mooring mast, it pulled the airship into Lakehurst's massive hanger, where it spent the night being refueled, cleaned up, and reinflated before taking off the next day back to Germany. The Hindenburg was so big, it could only fit in the Lakehurst Hanger with inches to spare. Ever since then, the Hindenburg made many transatlantic flights to the United States, most landing at Lakehurst.

Flight Season: 1936[]

The Hindenburg made 17 round trips across the Atlantic in 1936—it's first and only full year of service—with ten trips to the United States and seven to Brazil. Each of the ten westward trips that season took 53 to 78 hours and eastward took 43 to 61 hours.

Hindenburg’s fastest crossing of the North Atlantic took place in August 1936; the ship lifted off from Lakehurst, New Jersey at 2:34 AM on August 10th and landed in Frankfurt the next day, after a flight of just 43 hours and 2 minutes.

In May and June 1936, Hindenburg made surprise visits to England. In May it was on a flight from America to Germany when it flew low over the West Yorkshire town of Keighley. A parcel was then thrown overboard and landed in the High Street. Two boys, Alfred Butler, and Jack Gerrard retrieved it and found the contents to be a bouquet of carnations, a small silver cross and a letter on official notepaper dated May 22, 1936. The letter read: 'To the finder of this letter, please deposit these flowers and cross on the grave of my dear brother, Lt. Franz Schulte, 1 Garde Regt, Zu Fuss, POW in Skipton cemetery in Keighley near Leeds. Many thanks for your kindness. John P. Schulte, the first flying priest'. Historian Oliver Denton speculates that the June visit may have had a more sinister purpose: to observe the industrial heartlands of Northern England.

In July 1936, Hindenburg completed a record Atlantic round trip between Frankfurt and Lakehurst in 98 hours and 28 minutes of flight time (52:49 westbound, 45:39 eastbound). Many prominent people were passengers on the Hindenburg including boxer Max Schmeling making his triumphant return to Germany in June 1936 after his world heavyweight title knockout of Joe Louis at Yankee Stadium. In the 1936 season, the airship flew 191,583 miles (308,323 km) and carried 2,798 passengers and 160 tons of freight and mail, encouraging the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin Company to plan the expansion of its airship fleet and transatlantic service.

The airship was said to be so stable a pen or pencil could be balanced on end atop a tablet without falling. Its launches were so smooth that passengers often missed them, believing the airship was still docked to its mooring mast. A one-way fare between Germany and the United States was US$400; Hindenburg passengers were affluent, usually, entertainers, noted sportsmen, political figures, and leaders of the industry.

Hindenburg was used again for propaganda when it flew over the Olympic Stadium in Berlin on August 1 during the opening ceremonies of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games. Shortly before the arrival of Adolf Hitler to declare the Games open, the airship crossed low over the packed stadium while trailing the Olympic flag on a long weighted line suspended from its gondola. On September 14, the ship flew over the annual Nuremberg Rally.

On October 8, 1936, Hindenburg made a 10.5-hour flight (the "Millionaires Flight") over New England carrying 72 wealthy and influential passengers. Winthrop W. Aldrich. Nelson Rockefeller, German and American officials, and naval officers, as well as key figures in the aviation industry such as Juan Trippe of Pan American Airways. The ship arrived at Boston by noon and returned to Lakehurst at 5:22 pm before making its final transatlantic flight of the season back to Frankfurt.

Over the winter of 1936–37, several alterations were made to the airship's structures. The greater lift capacity allowed nine-passenger cabins to be added, eight with two beds and one with four, increasing passenger capacity to 70. These windowed cabins were along the starboard side aft of the previously installed accommodations, and it was anticipated for the LZ 130 to also have these cabins. Additionally, the Olympic rings painted on the hull were removed for the 1937 season.

Hindenburg also had an experimental aircraft hook-on trapeze similar to the one on the U.S. Navy Goodyear–Zeppelin built airships Akron and Macon. This was intended to allow customs officials to be flown out to Hindenburg to process passengers before landing and to retrieve mail from the ship for early delivery. Experimental hook-on and takeoffs, piloted by Ernst Udet, were attempted on March 11 and April 27, 1937, but were not very successful, owing to turbulence around the hook-up trapeze. The loss of the ship ended all prospects of further testing.

The last eastward trip of the year left Lakehurst on October 10.

Final Flight and Disaster[]

(Main Article-The Hindenburg Disaster)

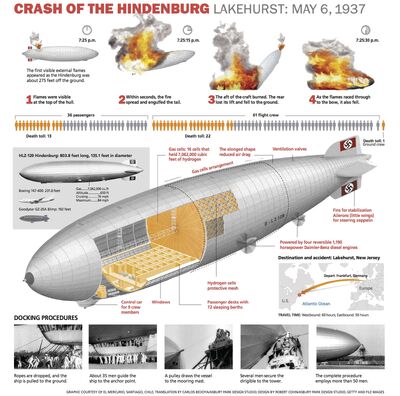

Hindenburg began its last flight on May 3, 1937, carrying 36 passengers and 61 officers, crew members, and trainees. It was the airship’s 63rd flight. The ship left the Frankfurt airfield at 7:16 PM and flew over Cologne, and then crossed the Netherlands before following the English Channel past the chalky cliffs of Beachy Head in southern England, and then heading out over the Atlantic shortly after 2:00 AM the next day.

Hindenburg followed a northern track across the ocean passing the southern tip of Greenland and crossing the North American coast at Newfoundland. Headwinds delayed the airship’s passage across the Atlantic, and the Lakehurst arrival, which had been scheduled for 6:00 AM on May 6th, was postponed to 6:00 PM.

By noon on May 6th the ship had reached Boston, and by 3:00 PM Hindenburg was over the skyscrapers of Manhattan in New York City. The ship flew south from New York and arrived at the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey at around 4:15 PM, but the poor weather conditions at the field concerned the Hindenburg’s commander, Captain Max Pruss, and also Lakehurst’s commanding officer, Charles Rosendahl, who sent a message to the ship recommending a delay in landing until conditions improved. Captain Pruss departed the Lakehurst area and took his ship over the beaches and coast of New Jersey to wait out the storm. By 6:00 PM conditions had improved; at 6:12 Rosendahl sent Pruss a message relaying temperature, pressure, visibility, and winds which Rosendahl considered “suitable for landing.” At 6:22 Rosendahl radioed Pruss “Recommend landing now,” and at 7:08 Rosendahl sent a message to the ship strongly recommending the “earliest possible landing.”

The airship arrived at Lakehurst at 7:15, facing strong headwinds and upcoming rain. The crew wanted to get the airship landed as soon as possible, so it could transport passengers back to Europe quickly for the coronation of King George the 6th. Communicating with the ground crew, the Hindenburg circled the landing field, trying to get it stable so it would be easier to dock. The winds made it complicated though. They couldn't get low enough to the ground, so the crew decided to attempt, a "high landing". In a high landing, the airship's landing lines are dropped from a higher height than normal and the ground crew would help pull the ship closer to the ground. As it flew lower to the ground, the main lines would be dropped and the airship would be dragged to the mooring mast, where a mechanism would pull the ship's nose towards it, making it easy to attach.

The engines were thrown into reverse multiple times and hard sharp turns were made to line up with the mooring mast. However, after these turns, the crew noticed something on the leveling scale. The ship was tail heavy.

At 7:25, without warning, the Hindenburg's hydrogen caught fire. Small flames ripped through the top of the ship, close to the tailfins. Five seconds later, the airship was rocked by a tremendous explosion as one of the rear hydrogen gas bags was ignited by the flames. The back of the airship was quickly engulfed in fire, and the ship (as it was losing hydrogen) began to fall to the ground tail-first. The tail imploded as it fell towards the ground.